An Eye on Spice

Meeting the need for rapid detection of synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists - introducing Chris Pudney (University of Bath, UK) and his portable analyzer

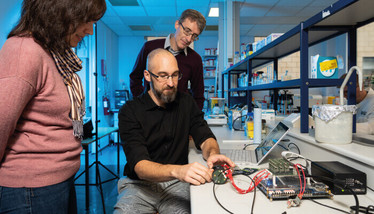

Pudney and colleagues testing the portable analyzer. Photo credit: The University of Bath.

What is your research focus?

We focus on synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, which are so-called “novel psychoactive substances” and collectively referred to as “Spice.” They mimic some of the active compounds in cannabis by interacting with endocannabinoid receptors, but do so with increased potency and exert enhanced effects. Interestingly, these compounds – which share some structural similarities with compounds from the plant – potentially also act on different receptors in the body, meaning their effects are difficult to predict.

The actual chemistry or strength of these products is often not known, which presents a serious problem – an accidental overdose of the wrong synthetic compound could lead to, for example, a stroke, or send them to the emergency room. It is also difficult to discern exactly what drug a patient on suspected Spice may have taken, so there’s an acute need for a point-of-care test from both health and harm reduction perspectives. That’s the overarching aim of our work.

How does it work?

The molecules in question fluoresce strongly, and we leverage UV excitation to capitalize on this by studying the detailed structure of the emission spectra obtained using fluorescence spectral fingerprinting – and piles of good old-fashioned math (1). What makes the method so effective for Spice analysis is this stepwise approach, whereby we identify synthetic materials and then apply numerical modelling to identify parent compounds and combusted materials. Such broad sensitivity allows us to cope with high levels of heterogeneity in the samples we process, but then we can also drill down into the details.

Techniques such as Raman and infrared spectroscopy are great for identifying specific molecules, but we are often faced with mixtures, which complicates the signal and complicates analysis. Coupled with the use of a biological medium, the challenge is intensified further. Despite the use of infrared as the de facto standard, it’s clear that new approaches are necessary for analyzing Spice and further synthetic compounds.

Where did the idea for the technology come from?

The idea came to me when I was working on a technology to predict protein stability. My partner is a psychiatrist and she asked me if the approach could be applied to detecting drugs, and I was surprised to find that the drug molecules resembled the chemistry of proteins I used for spectral fingerprinting in a number of ways. I tried it, and the initial lab results were promising. It was by serendipity that the team had a great relationship with the Avon and Somerset Police (UK). Soon we were working with seized materials from the police, and our method showed excellent discrimination between molecules in as little as five minutes using a saliva sample.

What makes the need so great for these specific compounds?

We have studied these molecules for many years – after all, they were once available through legal means in headshops on the high street. Eventually, however, serious side effects (violence, psychotic episodes, strokes and epileptic seizures, to name a few) emerged, and legislation adapted to move these poorly understood compounds out of public hands. Today, they’re still used largely in prisons and homeless communities because they’re readily available and incredibly cheap.

Our focus is not for application in law enforcement or detecting criminal activity – very specific chemical information is needed for such purposes. We are conducting this work with the aim of reducing the harm caused by these compounds in vulnerable communities. That’s the philosophy we share with collaborators at the University of Bath.

What’s next?

We have developed a robust and minute portable device prototype, which has acted as the much-needed proof of concept for making these measurements. The next stage is for us to make the analysis as user friendly as possible, and to demonstrate use in real-world settings. Troubleshooting will also be important before we can move the instrumentation into the hands of users.

In terms of instrument development, the next phase will be to use real samples – something we have been limited with thus far due to ethical and moral considerations – and to build our spectral libraries of how these drugs manifest themselves in different user populations, such as drug addicts and the homeless. Eventually, we’d like to give the technology away to charities and groups working with homeless people, and perhaps also sell it to companies and institutions to which it would have value.

I've always wanted a career in which I could practice my creativity, even when I worked on the assembly line in a fish factory. At one time, I channeled this need into dance, drawing, poetry and fiction, and I still do most of these things. But, following completion of my MSc(Res) in Translational Oncology and time working in labs and as a Medical Writer for major pharmaceutical companies, I'm happy to find myself in a career that allows me to combine my creative side with my scientific mind as the Deputy Editor of The Analytical Scientist.